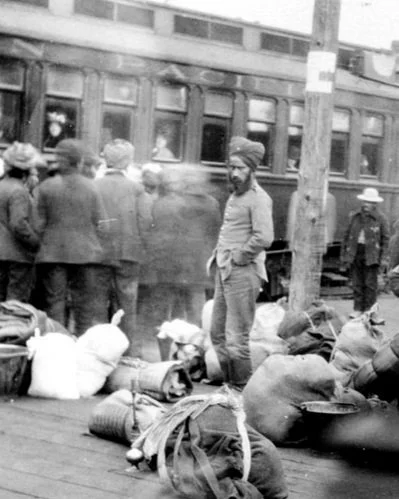

Sikh immigrants arriving on the SS Minnesota in Seattle | c. 1913 | Asahel Curtis | Washington State Historical Society, 1943.42.27255

Studio portrait of three Sikh men in Bellingham, Washington | c. 1905 | Henry Brown | Whatcom Museum of History and Art, 95.108.117

A Sikh mill worker who survived the Bellingham violence awaits a train to Canada | c. 1907 | University of Washington Archives, UW18744

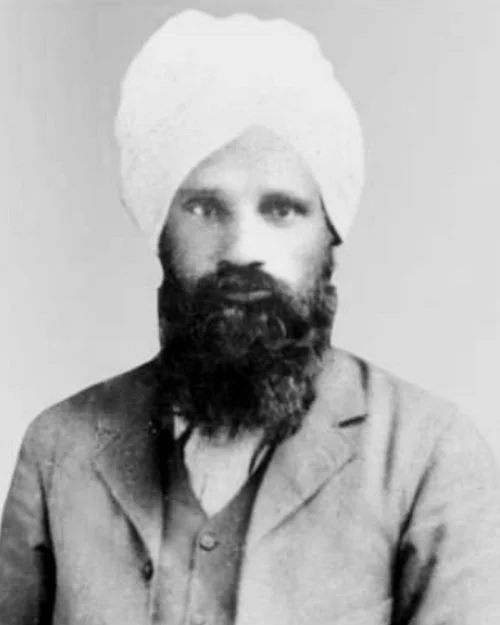

Portrait of the renowned Sikh anti-colonial revolutionary, Sohan Singh Bhakna, before leaving for his voyage to Seattle | c. 1908 | Library of Pacific Coast Khalsa Diwan Society

Sikh members of the anti-colonial Ghadar Party assemble at Stockton Gurdwara | c. 1913 | Library of Pacific Coast Khalsa Diwan

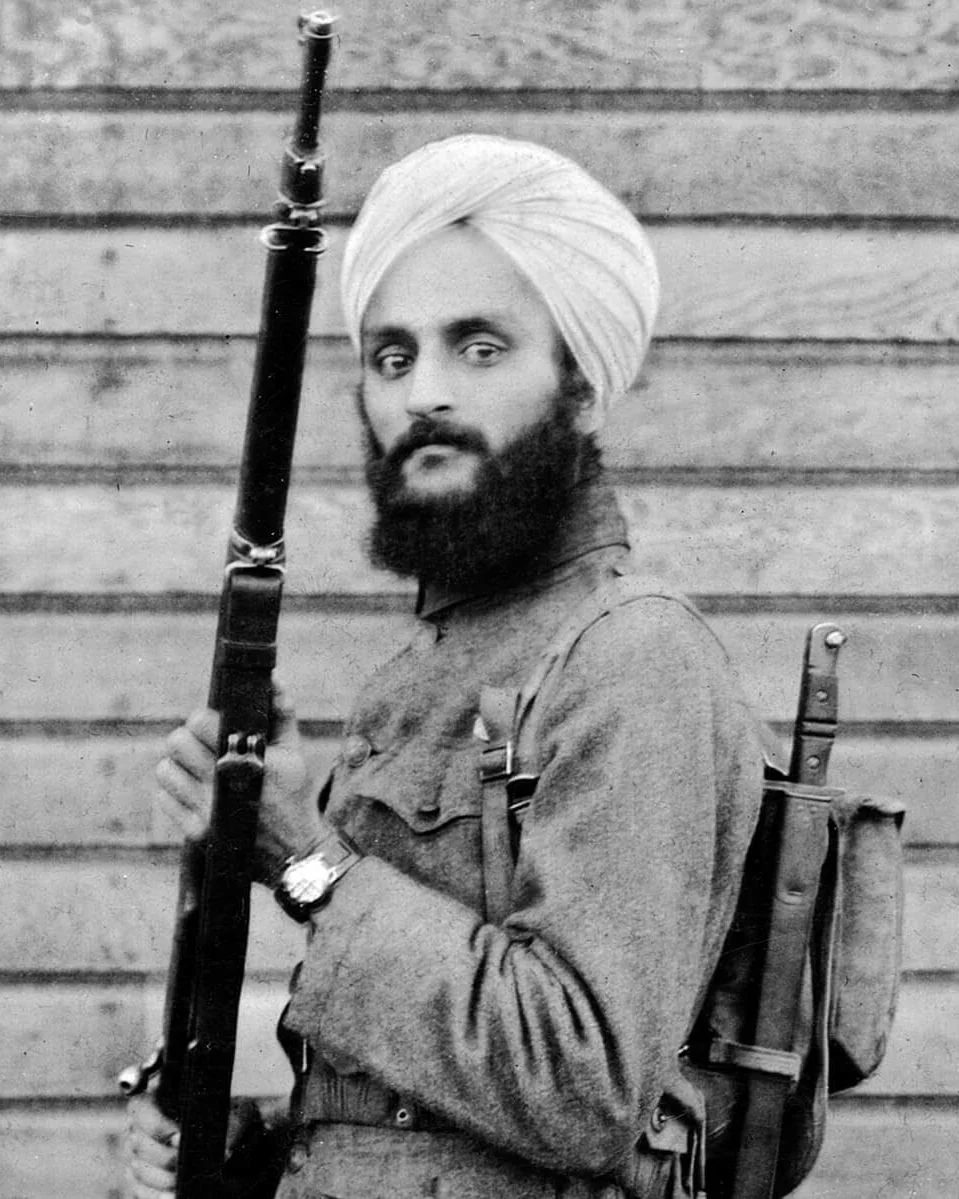

Bhagat Singh Thind during WWI, training at Camp Lewis in Southern Washington | c. 1918 | National Park Archives

Bombarded facade of Sri Akal Takhat Sahib, the highest Sikh seat of temporal affairs. The structure was destroyed by the Indian army in June 1984, marking the Sikh Genocide’s start

Embodying the spirit of Chardi Kala, a Sikh concept that signifies eternal optimism, the accomplishments of Sikh Americans today are a testament to the many struggles bravely endured by their previous generations

The Story of Sikhs in Washington

The first Sikh immigrants began arriving in the United States in the latter half of the 19th century, driven by political and economic pressures of British colonialism in India. The Pacific Northwest was often their first point of destination. Even today, many historians note that the credit for the development of the Pacific Northwest's lumber mills and railroads is owed to these early Sikh Americans. This is their story.

Most of the early South Asian immigrants to the United States were male Sikh laborers from Punjab, who entered North America through West Coast ports such as San Francisco, Astoria, Seattle, and Vancouver. They initially found work in agriculture, lumber mills, and railroad construction. However, due to legalized prejudice then prevalent in the country, Sikhs, like the Chinese and Japanese immigrants before them, began facing significant racism, intolerance, and bigotry upon their arrival. The distinct religious appearance of Sikh laborers, marked by unshorn beards and turbans donning their heads, made them visible targets, leading to instances of severe and systematic discrimination. One stark example of this hostility was the 1907 Anti-Sikh spree of violence in the state of Washington.

By 1907, a significant number of Sikhs had settled in the town of Bellingham, Washington (around eighty miles north of Seattle), working in lumber mills and quickly becoming valued by employers for their strong work ethic. “We cannot get white men who will remain steadily at their work,” one lumber mill owner had told the Bellingham Herald in 1906. “A large number [of white men] are transient and work only for whisky money leaving the company in the lurch just at the time that their services are most desired.” Observant Sikhs are prohibited from consuming alcohol, so by nature of their religious conduct they had little interest in “whisky money,” which resulted in Sikhs filling many jobs in Bellingham mills that soon angered the local population.

This resentment culminated on September 4th, 1907, when a mob of nearly four hundred disgruntled white workers, predominantly made of members of the Asiatic Exclusion League, methodically attacked Sikh homes and rounded up hundreds of Sikhs living in Bellingham. The Sikhs were then humiliated, beaten in the streets, and eventually forced out of the town. Many went north to British Columbia and others went south to California to find safety. Nevertheless, this date had become a major event in the dawn of the Sikh experience in America. The obstacles of hatred and prejudice, however, had not stopped at Bellingham as similar riots targeted at Sikh laborers in Everett, Washington had occurred on November 2nd, 1907. Such violent events, along with Anti-Asian laws that restricted land ownership and family reunification, significantly hindered the Sikh community's ability to establish itself in the Pacific Northwest.

The discrimination and violence Sikhs encountered in North America, reminiscent of colonial oppression in South Asia, catalyzed a political awakening among Sikh immigrants. Incidents like the Bellingham riots highlighted the parallels between the persecution Sikhs faced in America and the tyranny imposed on South Asians by British colonialism. This realization, stemming from the racism and white supremacy experienced by Sikhs both from segments of the American population and British colonial authorities, underscored the necessity of South Asian independence. Without freedom from colonial rule back in their homelands, Sikhs felt that they would never be able to find permanent safety from persecution that seemed to follow them globally. This gave rise to the Ghadar Party, a political movement aimed at overthrowing British colonial rule in South Asia through Ghadar or rebellion/revolution.

Predominantly composed of Sikh migrants, the Ghadar Party was a crucial force in the push for South Asian independence. United by the shared experience of displacement due to British colonialism and humiliation due to racial prejudice in America, the Ghadar Party created a space of solidarity from which collective diasporic activism could emerge. The Ghadar newspaper, a multilingual publication of the party, sought to awaken political consciousness around the importance of liberating their homeland from British colonial control. This movement, spearheaded by Sikhs primarily in the Pacific Northwest, Oregon, and California—many of whom entered through the Port of Seattle—ignited a widespread political awakening within the global Sikh diaspora. One such founder of the anticolonial Ghadar movement was the illustrious Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna who in April 1909 had landed in Seattle and from here had gone towards Oregon to work in Portland lumber mills.

These efforts led to significant Sikh mobilization along the West Coast, an example of which was the creation of the first Gurdwara in America, the Pacific Coast Khalsa Diwan Society, in the town of Stockton, California, in 1915. Popularly known as the Stockton Gurdwara, the institution became both the first spiritual center for early Sikhs in America and the operational base for the Ghadar Party's revolutionary activities. Many of the Stockton Gurdwara’s founders, like Baba Jwala Singh Thathian, Baba Visakha Didehar, and Baba Sohan Singh Bhakna would even leave their established farms and livelihoods in California to help the independence struggle back home. Scores of overseas Sikh activists of the Ghadar Party left from across the West Coast to assist the anticolonial liberation struggle in Punjab. Many of them never came back as they were later arrested or hanged by British authorities. Although the entire Sikh community did not depart, this event, combined with restrictive immigration laws, resulted in dwindling numbers of Sikhs in the Pacific Northwest.

An individual who would later become a prominent Ghadar Party activist and leave an important legacy in American constitutional history, Bhagat Singh Thind, also arrived in the United States through the Port of Seattle in this period. After his arrival in Seattle in 1913, Thind went on to work in the lumber mills of Oregon and became one of the earliest members of the Ghadar Party. He was also the first turban-wearing Sikh enlisted in the American armed forces in 1918 during World War I at Camp Lewis, Washington. After being honorably discharged as a veteran, he was granted naturalization by a District Court of Oregon but it was later revoked by the Oregon Bureau of Naturalization. Thind petitioned the judgment and the case ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The final ruling, Thind V. United States in 1923, ruled that because Thind was not white in the eyes of the common man, he was not white enough for American citizenship, and therefore the rebuking of his naturalization was legitimate. As a result of the ruling that only whiteness could constitute citizenship, the Justice Department began proceedings to de-naturalize Sikhs and Asian Americans at large who had previously obtained citizenship in lower courts. Since Sikhs were no longer considered citizens due to this Supreme Court ruling, they were not allowed to own land and remained disenfranchised for a significant period of their early American history.

The early struggles of Sikh immigrants, combined with restrictive immigration laws, led to a decline in their numbers in the Pacific Northwest until after World War II. In 1965, with hard-fought advocacy of many immigrant communities, the Immigration Act of 1965 was passed, which removed many discriminatory immigration policies and allowed for increased immigration by Sikhs from South Asia. Tragically, the next large wave of Sikh immigration would begin in 1984. From 1984 to the 1990s, the Indian state waged a genocidal campaign against the Sikhs in which upwards of approximately more than 150,000 Sikhs were killed. In response to the Sikh self-determination movement in the 1980s, the Indian state launched a brutal premeditated military assault on many sacred Gurdwaras of Punjab in June 1984, unleashed a calculated wave of countrywide anti-Sikh pogroms in November 1984, and executed mass killings in the form of enforced disappearances until the mid-1990s.

This period of ten years, from 1984 to 1994, is now remembered as the Sikh genocide by Sikh bodies worldwide. During this oppressive campaign of violence by the Indian state, many Sikhs sought refuge in North America in hopes of finding safety and starting a new life. The Indian state’s genocidal campaign had in many ways shaped the Sikh American diaspora as we know it in the modern age. Today, approximately half a million Sikh Americans primarily reside in California, New York, and Washington marking a community that has overcome considerable adversities, challenges, and traumas to establish itself in the United States. Washington, in particular, houses the third-largest Sikh population in America today and has enduring historical ties to the Sikh American experience.

Walking on the paths that the generations before them had paved, today, the Sikh Washingtonian community stands as an integral part of the Pacific Northwest, contributing richly to the cultural, economic, and social fabric of the state of Washington. Despite facing numerous challenges throughout their early history in America and continuing transnational repression from the Indian state in contemporary times, the Sikh American community at large has shown remarkable resilience and prosperity. Initially confronted with restrictive immigration laws and widespread discrimination, Sikhs navigated these hurdles with tenacity and a strong sense of community solidarity. Over the years, they have not only preserved their rich cultural heritage but have also thrived, contributing significantly to various sectors of American society. From their early history working in agriculture and lumber mills, Sikhs have expanded their influence into diverse fields such as technology, medicine, trucking, hospitality, politics, and many more. Their success is a testament to their entrepreneurial spirit, commitment to community service, and dedication to the Sikh principle of perseverance.